This year marks the 86th anniversary of America’s best-selling board game, Monopoly. And while many folks might fib about their age, Hasbro’s accounting of the game’s birth is quite the tall tale.

The true story is revived in a book by journalist Mary Pilon, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, just released by Bloomsbury. I also cover the game’s origins in my documentary PAY 2 PLAY: Democracy’s High Stakes, showing how a folk game was co-opted by a big company to become a billion-dollar industry.

I had set out to use a Monopoly metaphor to make the issues of campaign finance more relatable. Since practically everyone played the game in childhood, it has a nostalgic connection, though in hindsight it does teach some rather insidious lessons, such as felony crime. Anti-trust laws established over generations would make much of the behavior encouraged in the game illegal in real life. Between that and how Mr. Monopoly has come to symbolize the bankers and moguls flooding our elections with cash, I thought I had a pretty good metaphor to work into an essay film.

But it turned out to be just the beginning. I take you now to the sequence in my documentary that shows what real monopolization looks like: a company that asserts it has a monopoly on the very word “monopoly.” (I know: No one watches videos anymore. But this is really good, and it matters to the rest of the story. Besides, it’s way quicker than me condensing here.)

And we’re back! As you no doubt just saw, Monopoly was originally known as The Landlord’s Game, created by Lizzie Magie over 30 years prior to Charles Darrow’s claim that he invented a board game to feed his family during the Great Depression.

The story of Lizzie Magie and her intentions are important, because her goal for the game was to teach progressive economic theory, which got lost along the way. Worse still, she was dutifully conned out of attribution and money from Monopoly’s wild success. This recent New York Times article by Pilon tells the story of Lizzie and her vision of spreading the teachings of Quaker economist Henry George and his “single tax” theory.

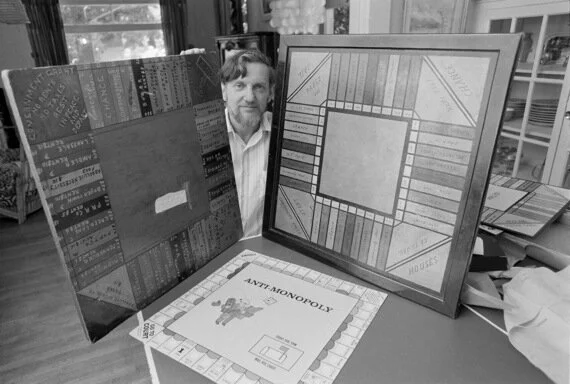

The usurping of The Landlord’s Game makes for a great meta-monopoly story, but even this turned out to be a story within a story. The real history may not even have been uncovered were it not for one tireless Ralph Anspach. An economics professor in the 1970s, Anspach thought a good way to teach anti-trust law would be to make his own board game, which he called Anti-Monopoly. As seen above, Ralph Anspach fought Parker Brothers for years over his game and its name, and in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court, the little guy prevailed, forcing the owners of Monopoly to settle. Ralph Anspach shared his remarkable story in a book called Monopolygate, alternatively released as The Billion-Dollar Monopoly Swindle. There could even be a movie in the works about Ralph’s comedic odyssey.

You can read more about the efforts to suppress the true history of Monopoly in the books cited above. But here I wanted to share a modern-day effort to rewrite the past that I encountered while making my documentary. It showed me that far from having little impact, documentaries can serve as a powerful record.

Ralph Anspach poses with original boards from The Landlord’s Game and his crreation, Anti-Monopoly.

When I finally got to sit down with Anspach, now in his 80s, I showed him a documentary that had just been released, Under the Boardwalk, a hagiography to Monopoly and its champions. The film was executive-produced by Phil Orbanes, who also appears in it as Monopoly’s chief historian. Orbanes was Parker Brothers Senior Vice President for Research and Development until the 1990s, before going solo to write books and articles about Monopoly as a full-time authority. A supposed expert on the Charles Darrow legend, Orbanes saw the myth he ardently peddled upended by Anspach’s revelations. Whereas Parker Brothers had been able to claim that Charles Darrow was the game inventor, Anspach had proved in court through depositions, testimony, and physical evidence that there had been a clear line passing The Landlord’s Game from a series of people before Eugene Raiford introduced the game to his guest Charles Darrow, even typing up the rules for him because he was so interested in this folk game that had been around. In fact, it was Darrow’s strict adherence to the game as presented to him that, years later, led to proof in court that he had essentially plagiarized everything.

All the street names in Monopoly come from streets in Atlantic City. The Landlord’s Game had been passed around for years with homemade game boards made out of oil cloths and wood, but it was only a group of Atlantic City Quakers in the 1920s that started naming the squares with their own street names. When Charles Darrow passed this game off as his own, no one seemed to wonder why a guy in Philadelphia came up with a game about Atlantic City property. Some might have wondered why, out of all the real street names, one of the names in misspelled: Marvin Gardens actually has an “e,” as in Marven Gardens.

It turns out that when Raiford obliged Darrow’s request for a written version of the game rules, the secretary who was typing it up made a typo. That Darrow used that misspelling verbatim, Anspach explained to me, can be used as evidence of plagiarism, because it removes the plausibility that Darrow did anything other than copy what he was given.

But there was so much more evidence: There were homemade game boards that predated Darrow’s boards, with the same squares such as “GO TO JAIL” and “PARK,” even with the same playing cards and play money. The game had been called “monopoly” commonly, with a lowercase “m” the way that “cards,” “chess,” and “checkers” are not capitalized. Darrow hadn’t even come up with a new name. Wisely, General Mills Fun Group, owners of Monopoly at that time, settled with Ralph Anspach in 1983 for an undisclosed amount.

So it was with great interest that Ralph watched the documentary I was showing him. With fun graphics, Orbanes and younger gamers describe how The Landlord’s Game was the predecessor to Monopoly, but it wasn’t until it reached Charles Darrow that he supposedly updated the game and named it Monopoly.

With amazement, Ralph reviewed the movie to watch again as his entire investigation was co-opted by Monopoly purists. “Wow,” he mused. “Orbanes is clever. You gotta hand it to him. Did you see what he did there?” Ralph fiddled with the remote to rewind the sequence. Ralph’s past as a professor never really left him, and he couldn’t help but teach. And even though he was in his 80s, I strained to keep up with him.

Ralph replayed the illustrated history sequence of Under the Boardwalk. With fun retro motion graphics, a little race-car playing piece from Monopoly zips over a map of America to indicate where the game had been played as The Landlord’s Game in various cities over the years — this, the timeline of Quakers, economics students, and neighborhood couples that Ralph Anspach had pieced together as a gumshoe trying to defend himself in court. While the timeline presented in Under the Boardwalk matches the revelations detailed in Ralph’s book, there was no attribution or mention of Ralph in this supposed historical record. Ralph did receive a request from a producer to be interviewed for a documentary about Monopoly, but after Ralph asked if their documentary was working with Hasbro, he never heard back. (I know this because Ralph was suspicious about my intentions when I reached out to him to interview him for my documentary, and it took some convincing that I genuinely wanted to tell his story.)

As Ralph replayed the scene from Under the Boardwalk, it began to sink in why there would be so much subterfuge and misrepresentation decades after Ralph won his lawsuit. “Orbanes is very clever,” Ralph mused again. Orbanes had incorporated all of the history uncovered and worked it into the new and improved official history of Monopoly. At the end of the timeline, however, the movie’s voiceover cheerfully concludes that it was when The Landlord’s Game was introduced to Charles Darrow that Darrow then took the game, made all the changes that are different from The Landlord’s Game, and then named it Monopoly himself.

Ralph had disproved the entirety of this claim in court. For one, Ralph had depositions from people who played the game decades before Darrow claimed to invent it, and they had referred to it as “monopoly” (seen in the clip above). Moreover, through the process of being passed on from player to player over the years, the changes to the game had been made by a number of people over time, including some of the most pivotal changes to the game that made it accessible to children. Ralph stressed the importance of Atlantic City Quakers who first set a fixed price for the properties as opposed to letting them go up for auction. This aspect made the game easier for kids to understand buying the property squares and also circumvented some un-Quaker-like actions such as raising one’s voice, as in quarreling, and lying about the value of something, since that value is changing every second.

Pointing his finger at the screen, Ralph asked me, “What is that? What is that called when a bunch of different people make contributions to a creative work over time? That’s the public domain.” It was starting to make sense to me now. In one fell swoop, the history of Monopoly had been rewritten to include the timeline Ralph had exposed while diluting what really unfolded in that timeline in order to buttress the legend of Charles Darrow.

In his book, Ralph stresses the importance of why Parker Brothers needs to burnish Darrow into a genius inventor: Parker Brothers needed to be able to have bought the game from someone in order to claim they own the game. In their early correspondence with Darrow, it was clear Parker Brothers knew about the preexistence of this game, confronting him in a letter while at the same time instructing him as to what details they would need from him in order to create a credible claim to patent. At the time, Parker Brothers had to work to remove Lizzie Magie’s imprint on the game. Today the owners of Monopoly work to remove the general public’s imprint on Monopoly, because if a billion-dollar industry could be considered in the public domain, why, anyone could go into that business — that is, if they could stand up to a monopoly.

Even in their PR materials today, Hasbro maintains that Charles Darrow invented the game, not even mentioning The Landlord’s Game (seen in the clip above, which I know you watched).

Making a documentary can be a lengthy, lonely affair, and once released, it can feel like the film disappears into the ether with little notice. But when you see history rewritten before your eyes, it’s an alarming reminder of how vital posterity is, because truth seekers in years to come will be putting together our story. What lessons they take away may not be in our control, but it is up to us to keep up the fight to spread the truth.